Henry Gunter

Tia Damali Kore Hortin (She/her)

Project Researcher & Activator

If I mentioned the name Roy Hacket, many of you might recognise him as the leading figure behind the Bristol bus boycotts. If I brought up the name Altheia Jones, you might recall the sight of the Mangrove Seven on your television screens. However, if I mention the name Henry Gunter, you might be drawing a bit of a blank? Well, I’ll give you a clue. He is connected to the TUC (Trade Union Congress). An organisation that’s located in a building that many of you may be familiar with, due to its central location within Birmingham…

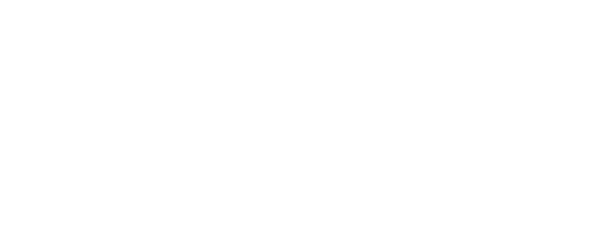

Henry Gunter was born in 1920 in Portland, Jamaica, and initially trained as an accountant before travelling to Central America. At the time, the USA was actively employing Jamaicans to work in the Panama Canal Zone, an opportunity not worth passing by. There, the young Gunter had his first experience with a racialised system.

The workers, referred to as Antilleans, were paid less than their white counterparts. Additionally, many of the upper management were employed from the Americas southern belt and were quite zealous in implementing a segregated workplace. All in all, this would’ve been – for lack of a better phrase – not the friendliest place of employment.

In 1942 he moved on to a wartime munitions factory in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where he began to make political and social waves. Gunter aggressively campaigned against the poor working conditions and racial discrimination that was rife at the time, with the eventual publication of a paper known as the Jamaican Worker. It was during this period of his life that Henry Gunter became familiar with the American Communist Party. This combination of communism, Black activism and unionism brought him to the attention of the FBI during the era of McCarthyism, which unsurprisingly ended in a visa denial.

Having been denied re-entry to the USA, Gunter eventually emigrated to the UK, settling in Birmingham and almost immediately joining the Communist party of Great Britain. In his own words:

"I have placed myself in the industrial heart of the country to meet more of the workers."

The Papers of Henry Gunter- Birmingham Archives

The situation in Birmingham, however, mirrored many other cities up and down the country. The 8000 – 9000 strong black population struggled to find adequate housing or employment. As one-man recounts:

"This is what he told me: I am sorry for you. It is a talent wasted, but the factories will not employ coloured men. Do not blame us. Blame the management, and they, in turn, will blame their employees. British workmen do not like sharing their benches with a coloured man, which is an end to it. I ask you, is that fair?"

Even those who could find accommodation and employment did not escape prejudice: with coloured shop stewards in one large Birmingham factory charged for the “privilege of working overtime”. Gunter’s experience was not dissimilar. His accounting skills were passed over, and one of his first factory jobs ended in a dismissal after he challenged the foreman’s racist views.

Based on his previous union experience, Gunter joined the Amalgamated Engineering Union and eventually became the first black delegate in Birmingham’s Trade Council. Through this platform, he was able to champion the rights of the city’s black workers, eventually, forcing the national Trades Union Congress to adopt a landmark resolution:

"Given the appalling conditions immigrant workers have to live under in Birmingham, we ask that the TUC demand that the government provide accommodation for the workers."