Shubeens and Shebeens

Tia Damali Kore Hortin (She/her)

Project Researcher & Activator

Birmingham has music deep in its DNA. Lack of conformity and thriving collaborative culture are deeply rooted in the city’s psyche, a product of its many waves of migration. This has created a distinct sense of individualism visible in the city’s people and the things they make; Music is far from the outlier. Yet despite this, Birmingham’s achievements are often left to the wayside, hidden behind the contributions of London and the Northern giants of Manchester and Liverpool. The unofficial slogan of we don’t shout enough about ourselves has never rung truer.

But let’s start at the beginning. Local performers like Danny King and Tex Detheridge put their own spin on the Rock and roll that dominated British airwaves. Venues like the Golden Eagle in Victoria Square furthered the evolution of the Birmingham music scene. The eclectic mix of soul, folk and blues eventually developed into the unforgettable Brumbeats of the 1960s.

Folk revival giants took influence from Brum writers like George Thomson. Whilst Modern Day psychedelic pop and techno still take influence from early labels like Network and Downwards records. Whilst, many of these artists were white, they drew inspiration from the development of Black American and Caribbean musical styles. This included soul, blues, and calypso, with the later additions of ska and reggae.

The city’s Black population had grown exponentially from 1948 onwards, with the economic boom of Birmingham providing a draw for people from many walks of life. Caribbean immigrants did not arrive in Britain with much, but the portability and emotional power of music meant that it was often brought with them. It provided a sense of home and belonging in their new country. Music was heavily spiritual and educative; it was a way to preserve Black history.

"We weren't taught at school. The music from Jamaica told us about our identity and culture. The positiveness. Things about Marcus Garvey, things about Malcolm x, anything you want to think about from Egyptology to the Israelites..it was embracing everything."

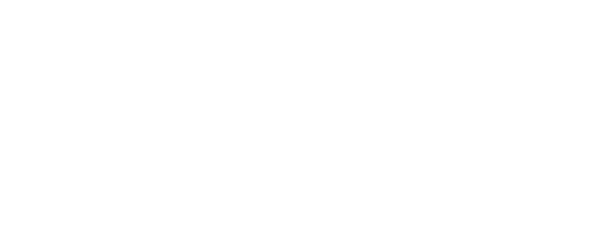

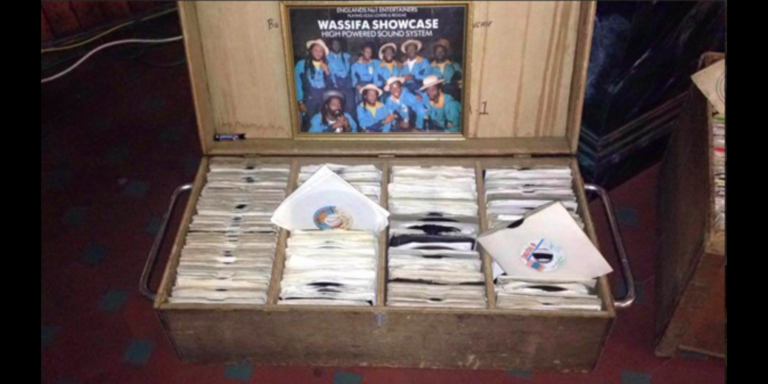

Wassifa, Apple podcast

However, the influence and inspiration mentioned previously didn’t always mean total acceptance, as Black audiences weren’t met with the same level of enthusiasm as their music.

"Sometimes I look at people...... and think do you know what it was like before. Do you know about having parts of Birmingham you can't go into? Do you know what it's like to leave clubs at night and be like it’s dangerous to walk home?"

Benjamin Zephaniah, Interview recorded at the Roundhouse, May 2022

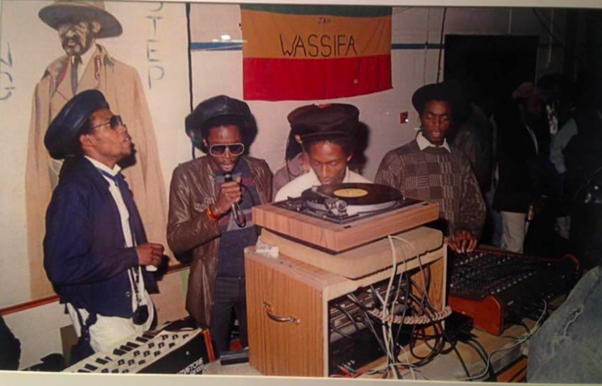

Consequently, people had to get creative. Blues parties were set up within community halls such as Winson Green community centre, churches, and even public buildings, with Steel Pulse performing one of their first gigs in a back room of Handsworth Library. The more illicit parties were known as shebeens occurring in a squatted house or someone’s back room.

These parties acted as focal points allowing young black people to express themselves freely and gather without fear of repercussions. Food and drink were available, but the most essential feature of these parties was the sound systems. Members played with homemade speakers, power amps and turntables until the early morning.

"At that time, we had no cars. We were walking to these places from Ladywood, from Winson Green, and we were walking to these places in Small Heath and Handsworth; anywhere the party was, we would go. We found out through word-of-mouth. Cuz there were no mobile phones, no YouTube, there was no internet, there was none of that. If you got to make a phone call, you were lucky. We were like street people. My mom would always say you don't live here; you live on the street."

Jacko Melody

"I think what was special about the parties was that we were creating a new type of culture, a new space. When we were home, our parents wanted us to be good little quiet Christians. They weren't really into our music. They had their old ska and blues.... but that wasn't rebellious enough for us"

Benjamin Zephaniah, Interview recorded at the Roundhouse, May 2022

Quaker City and Wassifa in Handsworth, Studio City in Small Heath, Duke Alloy in Sparkbrook and Sufferer in Ladywood are just some of the 100 sound systems that were around in Birmingham.

Popularity was contingent on remaining fresh, with systems tailoring their dubplates and competing in massive sound clashes to bring in the crowds. Unlike the blues parties in London, Bristol, and Manchester. Birmingham’s shebeens were much less segregated, enabling Black and white bands to combine musical influences and riff off each other. Two-tone was the product of such collaboration with the Birmingham-based bands UB40, the Specials and The Beat, benefiting from this underground scene.

"Birmingham was one of the few places left in Britain where it was still possible for a white man to get into a shebeen. Without wearing a blue uniform and kicking the door down."

Dick Hebdige.

Blues parties ebbed and eventually died out in the latter part of the 20th century with police crackdowns and the rise of Black establishments like the Hummingbird competing with them. But that is a story for a different article…